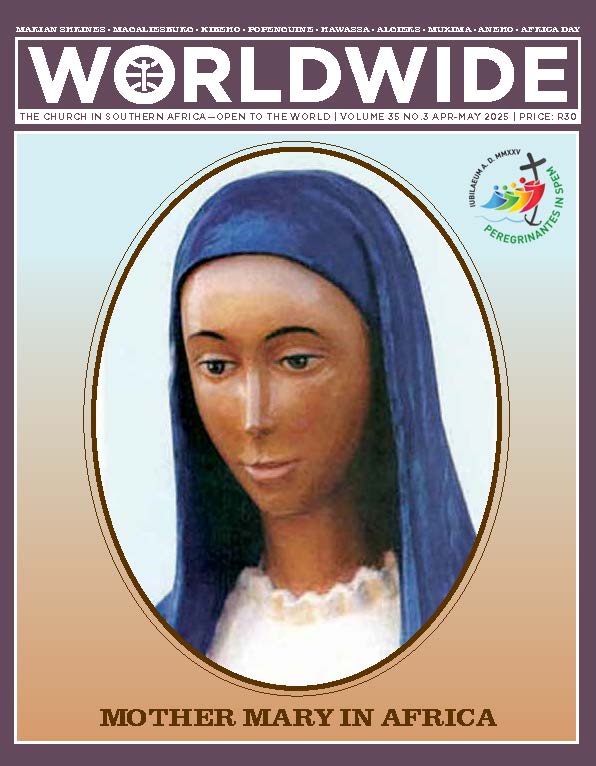

MOTHER MARY IN AFRICA

Head of the Statue of Mother Mary at Kibeho, Rwanda, carved by Marek Kowalski and based on the models of Jean Pierre Sibomana and Faustin Kayitana. In the statue, Mother Mary holds the Seven Sorrows Chaplet, a Marian devotion reintroduced to the Catholic community by Our Lady of Kibeho.

Kibeho is the only Marian apparition on African soil, officially recognized by the Church. Mother Mary’s requests for prayers preluded the 1994 Genocide.

REFLECTION • MARY TODAY

TRACING VARIOUS CONCEPTIONS OF MARY IN AFRICAN SPIRITUALITIES

This reflection aims to offer a framework for examining the theological patterns and gaps, along with tracing the colonial imprint of Mary, her place in Africa, and the reimagining of her role in our contemporary African society.

BY FABIAN ASHWIN OLIVER | YOUTH MINISTER, JOHANNESBURG

THE EXPLORATION of Mary in African spiritualities reveals a dynamic interplay between the past and present, where we must often go backwards in order to move forward. By tracing the earliest notions of Mary, we uncover fragments of her presence in African tradition, yet much work remains to be done to be able to fully understand her role in these contexts.

The Colonial Wound

To understand the image of Mary in Africa, one might begin by looking at the dual imagery encapsulated in the figure of Christopher Columbus. His 1492 voyage to the Americas, often remembered as the beginning of European colonization, also set the stage for the tragic and brutal shipping saga of the transatlantic slave trade. Central to this venture was Christianity, which became intertwined with the colonial project in complex ways. Columbus’s ship, named Santa Maria, serves as a powerful symbol of this fusion, linking the Virgin Mary with the mission of European expansion.

After discovering a second island in the Caribbean, Columbus named it Santa Maria de la Concepción (Holy Mary of Conception), further elevating Mary as a symbol of divine sanction for his journey (Athans 2022:7). Initially framed as a sacred mission, this connection later unfolded within a colonial enterprise that reshaped the religious, cultural, and social fabric of the Americas, Asia, and Africa, introducing Mary as both a source of spiritual solace and a reminder of the forces behind colonialism.

Christianity became intertwined with the colonial project in complex ways.

Even in regions where conquest was absent, but where relations were established through trade, such as in the Portuguese settlements in Africa and Asia, Mary was gradually integrated into the local cultures of converts, giving rise to new forms of Christian art. In these expressions, Mary was often depicted as an African or oriental woman, reflecting the blending of Christian iconography with indigenous cultural identities (Rubin 2009:xxv-xxvi).

However, apart from colonial endeavours, we must also harvest and tell our stories that predate the arrival of the missionaries. For instance, some academic evidence suggests that Christianity, and by extension the veneration of Mary, was already known and practiced in Africa prior to the arrival of European missionaries. For example, Emperor Zar’a Ya‘eqob (1434–1468) of Ethiopia mandated the reading of the Miracles of the Virgin Mary and decreed that she be honoured during many of the thirty feast days in the liturgical year (Ross 2022). This historical evidence points to a deep-rooted presence of Marian devotion in Africa long before the influence of missionary efforts.

Mary, an African

As institutional Christianity spread across Africa, Mary was not initially used as a public symbol of faith. However, within Catholic communities, such as those of the Bemba-speaking people of Zambia, devotional practices surrounding Mary gradually developed into a sacramental and mystical enhancement. Over time, Mary also took on political significance, with her figure becoming linked to local struggles and aspirations.

La Negrita became a symbol of hope and protection for those on the fringes of society, particularly Afro-Costa Ricans and indigenous people

The Bemba people sang hymns of Mary as a bright star who illuminated their lives and guided their path to Christ:

Bemba

Yambo we Lutanda

We ulange nshila

Ku benda mu mfifi

Uli ntungulushi

English

Hail, oh star

You who show the way

to those who walk in darkness.

You are our guide!

(Kumar 2015:6)

Mary was also understood in political terms, with a unique blend of biblical interpretations, such as those found in Revelation 12:1, where she was seen as part of the political resistance of the people:

Who is she!

Who comes forth

As the morning light

Beautiful as the moon

Bright as the sun

Terrible as an army

Set in battle array.

(Rubin 2009:420–421)

Indeed, as Mary met African converts, they were transformed into the deeper Marian identity. It can be argued that Mary was transformed into the African identity through her inculturation.

The story of Kimpa Vita illustrates this: born around 1684 in the Kingdom of Kongo, Vita became a significant religious leader who sought to merge traditional African spirituality with Catholicism. Her teachings included the radical assertion that Jesus, His Mother, and other key Christian figures were in fact Black and indigenous.

This “Africanized” version of Christianity challenged the established Church, as it directly confronted missionary portrayals of Christianity. Kimpa Vita’s beliefs led to her being labeled a heretic and witch by both the colonial authorities and the Church, culminating in her brutal burning at the stake in 1706 (Lamak 2022:7).

That Mary could be theologised as a Black woman has been an ongoing revelation around the world; certainly, one we must reflect on considering pertinent racism and patriarchy. Mary’s being of African descent is a phenomenon seen in the Black Madonnas around the world.

La Negrita (which translates “little Black one”) of Costa Rica, also known as Our Lady of the Angels, is a deeply significant religious figure, especially for the poor and those marginalized in society. The image of La Negrita, a dark-skinned Virgin Mary, is believed to have been found in the 17th century by a poor indigenous woman near the town of Cartago.

Over time, La Negrita became a symbol of hope and protection for those on the fringes of society, particularly Afro-Costa Ricans and indigenous people, who saw her as a reflection of their own identity and struggles (Vuola 2019:81–88).

Her significance goes beyond religious devotion; she represents resistance to colonial imposition and serves as a unifying figure for marginalized communities, offering a sense of dignity, solidarity, and divine care.

Muma Maria: (Re)Thinking Mary Today

As I reflect on the rethinking of Mary in Africa, I see her as both a significant spiritual figure and supreme ancestor, deeply aligned with African spirituality and working in the invisible world alongside other African saints.

She influences the betterment of African life, always drawing us closer to God’s divine love, not as a distant figure, but as one who actively participates in the spiritual and material struggles of the people.

In Africa, Mary is frequently portrayed as a mother with a child with less focus on her virginity. This could be explained by most Africans’ primary concern for and focus on childbearing and the taboo surrounding childless or barren women (Oduyoye 1996:108).

Mary becomes a powerful force for transformation, urging us to break the silence, resist oppression, and work toward the betterment of our communities in alignment with God’s divine love.

Without romanticising motherhood or child-rearing, the maternal images of Mary resonate with those who know the pain of broken-heartedness, especially mothers who have lost children to the systems of death or violence, or whose children are unjustly punished by the state.

Mary’s deep connection to these experiences of suffering brings her closer to the lived reality of many African women fleeing wars, fighting inequality, and seeking better lives for their loved ones.

Mary is a reminder of God working behind the scenes at every stage of our lives, even when it seems that all hope is lost.

It is time to rethink Mary’s traditional role of glorified subservience, a perception that often leads to women enduring violence and remaining silent, accepting injustice as part of their fate.

We should instead embrace Mary as a prophetic figure, as portrayed in the Magnificat—protesting against the brutal oppression of women around the world.

Rethinking Mary means understanding her in the context of Africa, not as a passive figure but as one who challenges imperial notions that have historically led to the demise of Africans.

Mary, as our mother, offers an invitation to listen to and follow Jesus, who leads us in love, justice, and peace.

In this way, Mary becomes a powerful force for transformation, urging us to break the silence, resist oppression, and work toward the betterment of our communities in alignment with God’s divine love.