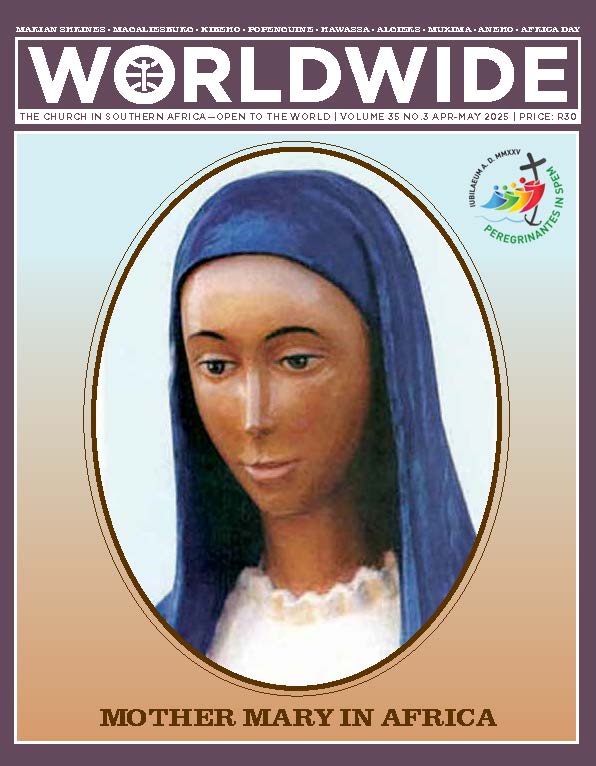

MOTHER MARY IN AFRICA

Head of the Statue of Mother Mary at Kibeho, Rwanda, carved by Marek Kowalski and based on the models of Jean Pierre Sibomana and Faustin Kayitana. In the statue, Mother Mary holds the Seven Sorrows Chaplet, a Marian devotion reintroduced to the Catholic community by Our Lady of Kibeho.

Kibeho is the only Marian apparition on African soil, officially recognized by the Church. Mother Mary’s requests for prayers preluded the 1994 Genocide.

INSIGHTS • INFLUENCING LEGISLATION

OUR VOICES WERE HEARD

The Catholic Parliamentary Liaison Office (CPLO) has devoted itself, for more than 27 years, to foster improvements in laws intended to be approved by the Parliament making them more beneficial for the lives of the citizens. In recent instances, on the Expropriation Act, the CPLO has achieved that its voice be heard incorporating, in the drafting of the Bill, significant elements.

BY MIKE POTHIER | PROGRAMME MANAGER, SACBC PARLIAMENTARY LIAISON OFFICE, CAPE TOWN

WHEN THE CPLO was established in 1997, one of our main tasks was to make submissions to the National Assembly and the National Council of Provinces, trying to influence the final outcome of the laws from Parliament. Our primary approach has always been to question whether or not a proposed law serves the common good, respects human rights, and is likely to bring about improvement in people’s lives.

Over the years, we have often been asked whether we ‘actually’ or ‘really’ influence legislation; does our work result in identifiable changes to the wording of laws? Many people assume that MPs simply go through the formalities of holding public hearings, and then do whatever they want. So, the answer to the question may surprise them: yes, we do contribute words and phrases that improve laws, and we succeed in getting undesirable provisions removed, or at least mitigated. Sometimes the impact can be slight; sometimes it is significant.

Expropriation Act: Mediation

The Expropriation Act 13 of 2024, recently signed into law, provides a good example of how the CPLO contributed some clear improvements to the text of a law.

The Expropriation Bill was introduced in 2015 and public hearings were held over three days. At this point we made a submission which raised, inter alia, the question of property owners having to approach a court if they were unhappy with the compensation offered. We suggested that some form of mediation should be provided for, as it is usually a cheaper, quicker and more accessible form of dispute resolution.

As it happens, that Bill was withdrawn by the government in 2018, but it was soon followed by a new Draft Expropriation Bill, published by the Department of Public Works. We were pleased to note that this draft contained a provision for mediation in cases of disagreement—exactly what we had suggested three years earlier. (No one would argue that in South Africa law making is a swift process!)

The process by which laws are made in South Africa encourages the involvement of civil society. It is open and transparent and public inputs are taken seriously.

Public purpose and abandoned land

Two years later a further version of the Bill was introduced into Parliament, largely reflecting the department’s draft Bill. The CPLO made further submissions on this version, including two points:

Firstly, we noted that the definition of ‘public purpose’ was an extremely wide one: “any purposes connected with … the provisions of any law by an organ of state”. We suggested that this needed to be tightened up so that expropriation would only happen if it was truly to the benefit of the public.

Secondly, we commented on the clause that allowed for expropriation without compensation, where an owner had abandoned the land by failing to exercise control over it. We argued that “there are situations where owners cannot exercise control over their land due to forces beyond their control—land invasions or unlawful occupations of buildings, for example. This clause should make it clear that only voluntary abandonment of land is intended as a ground for expropriation without compensation.”

The Bill then went through a lengthy process of debate and public hearing sessions, after which a new version was released. Among its changes was a new, and tighter, definition of ‘public purpose’—the new definition read: “‘public purpose’ includes any purposes connected to the administration of any law by an organ of state, in terms of which the property concerned will be used by or for the benefit of the public.” Any public purpose expropriation would have to demonstrate its public usefulness or benefit. Again, this was just what we had asked for in our submission.

Civil society involvement

The matter of abandoned land was also dealt with. The relevant clause was changed to read, “where an owner has abandoned the land by failing to exercise control over it despite being reasonably capable of doing so.” The proviso ‘despite being reasonably capable of doing so’ very closely equates to the idea of ‘voluntary abandonment’ in our submission.

This brief overview reveals how one organisation—in this case the CPLO—was instrumental in achieving three improvements to the Bill. Each of them, we would argue, made the final Act better and more respectful of people’s rights. Numerous other groups did exactly the same, highlighting other aspects and suggesting other changes. The process by which laws are made in South Africa encourages the involvement of civil society. It is open and transparent and public inputs are taken seriously. Not everyone will be happy with the outcome (as the ongoing controversy over this Act shows), but no one can claim that their voices—if they took the trouble of raising these—were not heard.