PROFILE • FR RONALD CAIRNS OMI

Light in the Dark City

Parish priest of St Hubert, Alexandra, for forty years, Fr Cairns made a remarkable impact on the lives of so many people in the community through his commitment in favour of justice, peace and reconciliation

BY Marian Pallister | Chair of Pax Christi Scotland

THEY CALLED it “the dark city”, perhaps not the most encouraging label which was stuck firmly to the parish where Fr Ronald Cairns OMI was posted as pastor. However, in 1981 and hardly a decade into the priesthood, at just 35 years old, that was the situation in which he found himself. Appointed to the township of Alexandra on the outskirts of Johannesburg; a challenging parish at the start of what would be a hugely confrontational decade of apartheid, Fr Cairns never let the darkness obscure his mission to create a just world.

The word discrimination is defined as ‘the unjust or prejudicial treatment of different categories of people, especially on the grounds of race, age, sex, or disability’.

The fact that Alexandra had no electricity supply (hence the dark city label) was an outward symbol of the harsh, deeply ingrained injustices experienced by Fr Cairns’ new parishioners. A white priest landing in such a township could have fared badly—he might even have petitioned his superiors to remove him to somewhere safer, less violent, less subject to the police harassment suffered by a black population under that cruel regime.

Prophetic voice

Instead, Fr Cairns, or as his parishioners came to know him, “Fr Ronnie”, stayed, becoming a champion in the struggle to end apartheid and subsequently a defender of all those facing the immense challenges Alexandra continues to experience. He died while still leading that flock, forty years after his appointment to St Hubert.

It is perhaps ironic that St Hubert is the patron saint of hunters. In those early years in the parish, Fr Cairns found that his parishioners were the hunted, accused of acting under the influence of outside agitators. He would speak up for them then—in court when necessary—and in the post-apartheid years, he would continue to be a voice for those suffering the socio-economic problems and the unrest that would be ever present in the township. Before the Covid pandemic hit, he was still making headlines by bringing yet again the injustices still experienced in Alexandra under public scrutiny.

They say he wouldn’t have chosen to live anywhere else.

Background

He had been raised in Randfontein, with its ‘gold rush’ past (and a far nobler background blended from history dating back to the second half of the 16th century when the AmaNdebele lived as one nation under King Mhlanga). An only child, Ronald Cairns was born on 3 October 1946 to a Scottish Presbyterian father, Hascott Cairns, and Norah, his German-born Catholic mother. Norah became the religious influence in his young life.

He was ordained on 14 January 1972 by Right Rev. Bishop Anton Reiterer MFSC (Missionary Sons of the Sacred Heart, initials in Latin), and was quickly appointed regional director of the Christian Life Group and vocations director for the Oblates of Mary Immaculate. In the ensuing years, he became the Episcopal Vicar for Aids, Dean of the Northern Deanery and Provincial of the Oblates, Northern Province. He served in a number of parishes in the diocese before that life-changing move in 1981 to Alexandra.

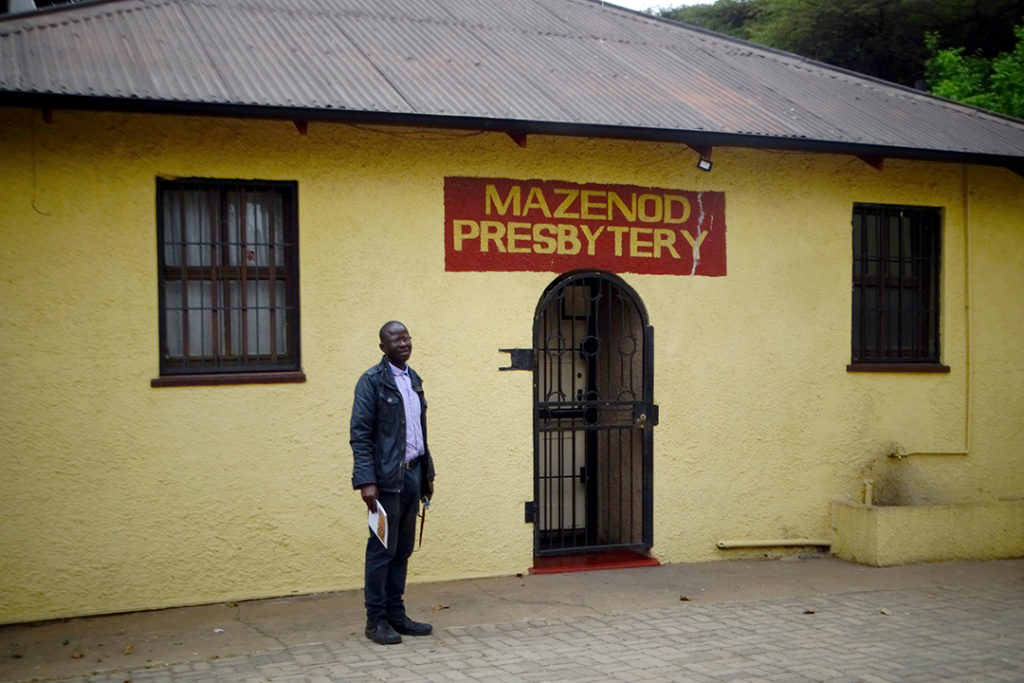

standing at the door. Credit: Worldwide.

Out-reaching and ecumenical approach

Parishioner Maria Maoba explains that when he arrived at St Hubert, it was at the height of the political uprisings. Under such circumstances, it would have been easy to say Mass and stay put in the parish house, but Maria says that Fr Cairns went door-to-door, visiting all Catholic families in the township, those practising and lapsed. This, she says, helped to rebuild the parish. He also put out his hand to ministers of other denominations, which led to the formation of a Ministers’ Fraternal for all clergy in Alexandra.

This young white priest made his mark early by reaching out to the whole community, not just Catholics, and standing by them in the most difficult of times. By 1984, just three years into his ministry in the parish, the community had such respect for him that they asked him to intervene in what Maria Maoba describes as a war between two taxi companies.

Alexandra’s Six Day War

In 1986 Fr Cairns’ name reached a wider audience. In February of that year, Alexandra declared war on the apartheid regime—a situation that became known as Alexandra’s Six Day War. Young people died and there were mass funerals conducted by the Ministers’ Fraternal. St Hubert was at the centre of the troubles, and Fr Cairns was harassed and detained by the regime for helping young people who sought shelter from the police.

Reports of the situation were given by Michael Parks in the Los Angeles Times, who wrote of the support offered by 300 white South African protesters —certainly a newsworthy situation at that time—who defied police orders that barred them from the ‘riot-torn black township’. They were welcomed by thousands of black Alexandra residents when they arrived to lay flowers on the graves of the victims that Fr Cairns and fellow members of the Ministers’ Fraternal had laid to rest.

One of the white organisers, Morris Smithers of the Johannesburg Democratic Action Committee, said: “These fallen comrades will never live in a free South Africa, but their sacrifice has helped ensure that future generations will.” Father Cairns responded: “We do not see colour. We see each other as brothers and sisters.”

The police had been particularly violent, and were responsible for Alexandra’s death toll and very clearly did ‘see colour’, as they merely watched this intervention by the white protestors, only firing off tear gas to disperse the crowds when the buses took the campaigners home.

Forced removals

The residents of Alexandra had no history of peace to fall back on, no solid rock on which to rebuild. The kind of violent harassment that they were subjected to stretched back for decades. There had been forced removals in the 1940s, the boycotts of the Bantu Education Act in the 1950s in which Alexandra teachers lost their jobs. There were violent attempts to wipe Alexandra off the map completely, but the township was given official status as a residential area in 1982, and there was a fancy ‘master plan’ to turn the dark city into a garden city. The Six Day War in February 1986 put an end to that, with 40 people killed. The collapse of the council was followed by the setting up of street committees and peoples’ courts.

In June of that year, a national state of emergency was declared and the apartheid regime began an Urban Renewal Plan, which in effect meant demolishing dwellings in areas of unrest. Much of the Alexandra population was displaced and there were two treason trials. Fr Cairns spoke for the defence at one of them, earning himself a place in Richard Abel’s book, Politics by other means: law in the struggle against Apartheid 1980–1994 (published by Routledge). Abel records that Fr Cairns testified on behalf of community leaders.

For Alexandra, this was the norm and the1990s brought little let-up in the violence and harassment, the poor living conditions and the displacements—a norm that nonetheless produced a president, Nelson Mandela, who was at one time a resident in the township.

Maria Maoba describes the 1990s as “one of the darkest periods of our history”. She explained that for four consecutive years, most of St Hubert’s parishioners were displaced, some seeking sanctuary in the church itself. She said, “The community came to Father and requested his intervention as the police were brutally killing people in Alexandra.”

Peace and community builder

She added that in 1993, Fr Cairns was asked to lead the process of bringing peace to local political parties as many people had been killed. A peace accord was subsequently signed, thanks to Fr Ronald Cairns OMI.

Lorato Phalatse, another of this remarkable man’s parishioners, said, “Fr Cairns had a very clear approach and outlook on life based on strong and deeply ingrained moral principles. He had a clear sense of right and wrong and good and bad that was rooted in his faith. One always knew without any doubt what his position was on any issue. Furthermore, he really had the courage of his convictions and lived by them with no fear or favour.”

Remarkable for many reasons: putting community politics aside, he was still intervening in taxi wars in 2018, mediating peace and achieving the signing of a memorandum of understanding between the warring parties. This was a priest who moulded a parish and a community.

Lorato Phalatse said, “Over the 40 years that he lived at St Hubert’s, Fr Cairns built a strong congregation of believers and a parish that in all aspects of our faith could hold its head up proudly in spite of being one of the poorest communities in South Africa. He built solid institutions on the Church campus that took care of children at St Martin De Porres Crèche and the elderly at Joseph Gerard Old Age Home, and outreach programmes such as Kgolofelo ya Josef that reached out to the indigent in Alexandra with the weekly distribution of food parcels.”

He could sort out an argument, never taking sides but bringing the complainants together to sort things out. However, he was not perfect—which saint ever was? Even at his Requiem Mass there was mention of his quick temper (that red hair, that Scottish father…). His parishioners, however, stress that his volatility was softened by the fact that once his grievance was aired, he returned immediately to smiles and laughter. Perhaps he needed that steeliness to help him address the many overwhelming difficulties faced during those four decades in Alexandra.

Positive imprint

There was clearly a Cairns charisma that worked its own little miracles, from defusing the violence during apartheid to influencing the youth in his parish. Paulos Mngomezulu explained that Fr Cairns created structure in the lives of children and young people, offering them the ear that absent biological fathers denied them, as well as creating activities and groups in which they could learn to become negotiators and leaders like him. Zakhele Lengoati said, Fr Cairns “…played an incredible part in our lives at a very crucial stage in our growing process”.

This man of mission sadly passed away after unexpected health complications on 6 February 2021. Alexandra is clearly still in mourning for a man who steered them through so much. As Lorato Phalatse explained, “He continues to be sorely missed, but he left us with strong values and principles of our Catholic faith that will sustain us for the rest of our lives.”

A fitting legacy.