YOUTH VOICES

A PLACE TO CALL HOME

‘Home is where the heart is’, as they say, is not bound to a physical space or a specific situation, but it is more about our willingness to get involved in reality and the people with whom we live

BY JILL A. WILLIAMS | CANDIDATE LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT, PRETORIA

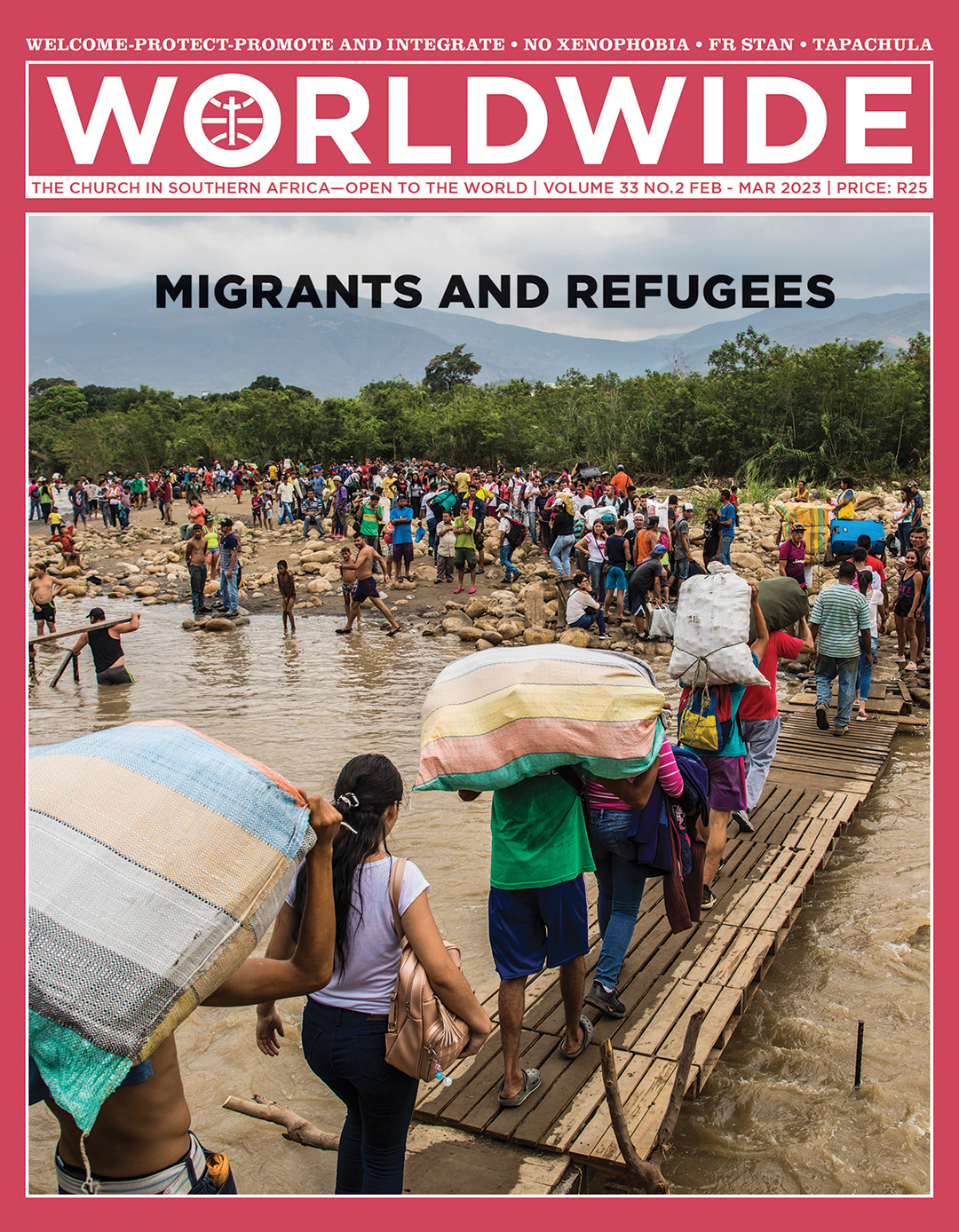

WHEN WE think of immigration and becoming a refugee or an asylum seeker in a foreign land (and all that goes with it), it sounds like something out of a suspense-filled drama or a thriller; something that happens out there and not in one’s own circle. From the political

tumult in one’s country or region, to the upheaval in one’s city and possibly one’s home, it becomes increasingly impossible to stay rooted, to stay sane and positive about something good coming out of such a situation and for an end to the unrest. Fleeing is the only solution. Run and survive or stay and die. According to the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR), about 100 million individuals as of May 2022 faced similar displacements worldwide—10.7 million more than in 2021, most probably due to the war in Ukraine amongst other causes (UNHCR 2023).

Searching for a new home

Jesus, Mary and Joseph similarly experienced a period of unrest soon after the glory and splendour of the Nativity. Matthew 2: 13 recalls it: ‘Now after they had gone away, behold, an angel of the Lord appeared in a dream to Joseph, saying, “Get up, take the child and his mother and flee to Egypt, and stay there until I tell you. For Herod is about to seek the child to destroy him”.’ Soon after experiencing the beauty and joy of a new life, the terror of death was now on the heels of the Holy Family. The instruction was simple: flee. They found refuge in Egypt, a land which once was a place of slavery for their people. There they were safe and could enjoy their new life as a young family. Yet, they had to stay alert, to lie low and wait. For how long? Only God knew. Mary and Joseph might have echoed the words of Charles Dickens in his historical novel, A tale of two cities, ‘It was the best of times, it was the worst of times… it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair’ (Dickens 1859).

a good plan in store for them. Credit: Pascal/Pixabay.

We all experience this dichotomous journey sometimes in our own lives, in some form or another. A family who was left homeless after a flood hit their town, making their way to a shelter for aid; a drug addict taking the first brave steps to a rehabilitation centre; an ostracised church-goer moving to a new place of worship; an overworked and underpaid employee attending an interview for a new job; an emotionally abused person breaking ties with their abuser or even a boy being initiated into manhood. At times, this new ‘home’ is a temporary physical or mental residence which provides the peace and shelter needed as we plan for our next step in life; at other times, it becomes a place where we settle permanently, as we see ourselves having better opportunities in the new place. The journey is long, and not without its own set of challenges. The new ‘home’ is filled with possibilities, but also many hurdles to overcome—a new language, a new culture, a new start.

Getting involved

I was introduced to the term flâneur a few years ago—a strolling wanderer who looks and observes, not really participating in the activities being observed. This French term is usually associated with

the elite or middle class—a pastime of the well-off. Sometimes we do this in our social circles—looking at and observing people and situations, but not getting too involved by getting to know them on a deeper level. This means we avoid immersing ourselves in alternate

realities and experiences. We are all on a journey, whether or not this is in haste or to another physical country or land. Why then are we so afraid of involving ourselves in ‘the other’, the unknown? Perhaps we are afraid that we might just find that we too are sojourners and strangers in this world, that it is not our permanent home (1 Peter 2: 11).

Credit: Joe/Pixabay.

Jesus walked this earth, a stranger living amongst His own people; His own Creation. He travelled and observed, but also participated in the joys and sorrows of the people He lived amongst. He knew that His time on earth was a temporary journey to an everlasting home with His Father. Yet even in His being seen as a strange, yet wonderful teacher by the people with whom He dwelt, He stooped down to the lowest in society and dined with them. Like Jesus, in order to call the land ‘home’, even just for a short while, one must immerse oneself in it—not only observing life but living it.

Jesus travelled and observed, but also participated in the joys and sorrows of the people He lived amongst

Nothing in life is guaranteed and the security of our present situation can be changed in an instant, as we all experienced in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. We each are a moment away from experiencing the distress and confusion of displacement— the tormenting thought of leaving the known to enter the unknown—even when we convince ourselves and hope beyond all hope that nothing bad will happen to us. Yet there is hope in any affliction—the realisation that you are not alone; that great opportunities lie ahead and that there is something better waiting you.

Displacement

This was the experience of the people of Israel, who were taken as captives in Babylon—somewhat the opposite experience of the refugee or immigrant. They lived happily in their land, their home, yet were forcibly removed and made to live in Babylon. By the rivers of Babylon,

by Bob Marley & the Wailer (Song Lyrics 2023), echoes Psalm 137 and the story of the Israelites in captivity: “By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, ye-eah we wept, when we remembered Zion. When the wicked carried us away in captivity. Required from us a song, now how shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?” Although this was a move from a time of peace to a period of unrest, there are some similarities with the experience of an immigrant: the feeling of displacement and having to acclimatise to a completely new way of life in a new environment (and amongst new people). The exiled did not know if they would ever see Israel again or be able to eat the fruit of the land. The future seemed bleak.

Like Jesus, in order to call the land ‘home’, one must immerse oneself in it—not only observing life but living it

However, after being taken captive by the Babylonians under the rule of King Nebuchadnezzar, the Israelites were given a sign of hope through a letter given to the King, which was written by the prophet Jeremiah, addressed to the Israelites: “Build houses and dwell in them; plant gardens and eat their fruit. Take wives and beget sons and daughters; and take wives for your sons and give your daughters to husbands, so that they may bear sons and daughters—that you may be increased there, and not diminished. And seek the peace of the city where I have caused you to be carried away captive, and pray to the Lord for it; for in its peace you will have peace” (Jeremiah 29:2–7). God wanted them to call the new land their home. He wanted them to continue living, working and worshipping Him as they used to, with hope in their hearts, so that through their lives they would glorify God and not their captors.

Open and welcoming home

Furthermore, the prophet gives this Word from God: “I alone know my purpose for you, says the Lord: wellbeing and not misfortune, and a long line of descendants after you” (Jeremiah 29: 11). Although the enemy had planned for the captive and the refugee to remain in the shadows, unloved and unknown, God still has a good plan in store for both. Ultimately whatever period of transition or journey to a new physical, mental or even spiritual territory that you may face, God knows where you need to be. Where you are right now is exactly where you should be. One priest said it this way: “Die Here is Die Here, en Die Here weet.” (The Lord is The Lord and The Lord knows). In all times and situations, we should emulate our Lord in glorifying God, as we are called to do: “Do not be anxious, but in everything, make your requests known to God in prayer and petition, with thanksgiving. Then the peace of

God, which is beyond all understanding, will guard your hearts and your minds in Christ Jesus.” (Philippians 4: 6, 7). In this way, we will succeed in reaching out to the ‘other’ in their time of displacement and upheaval, inviting even the unloved and unwanted to call our hearts Home.