YOUTH: VOICES OF HOPE IN SOCIETY

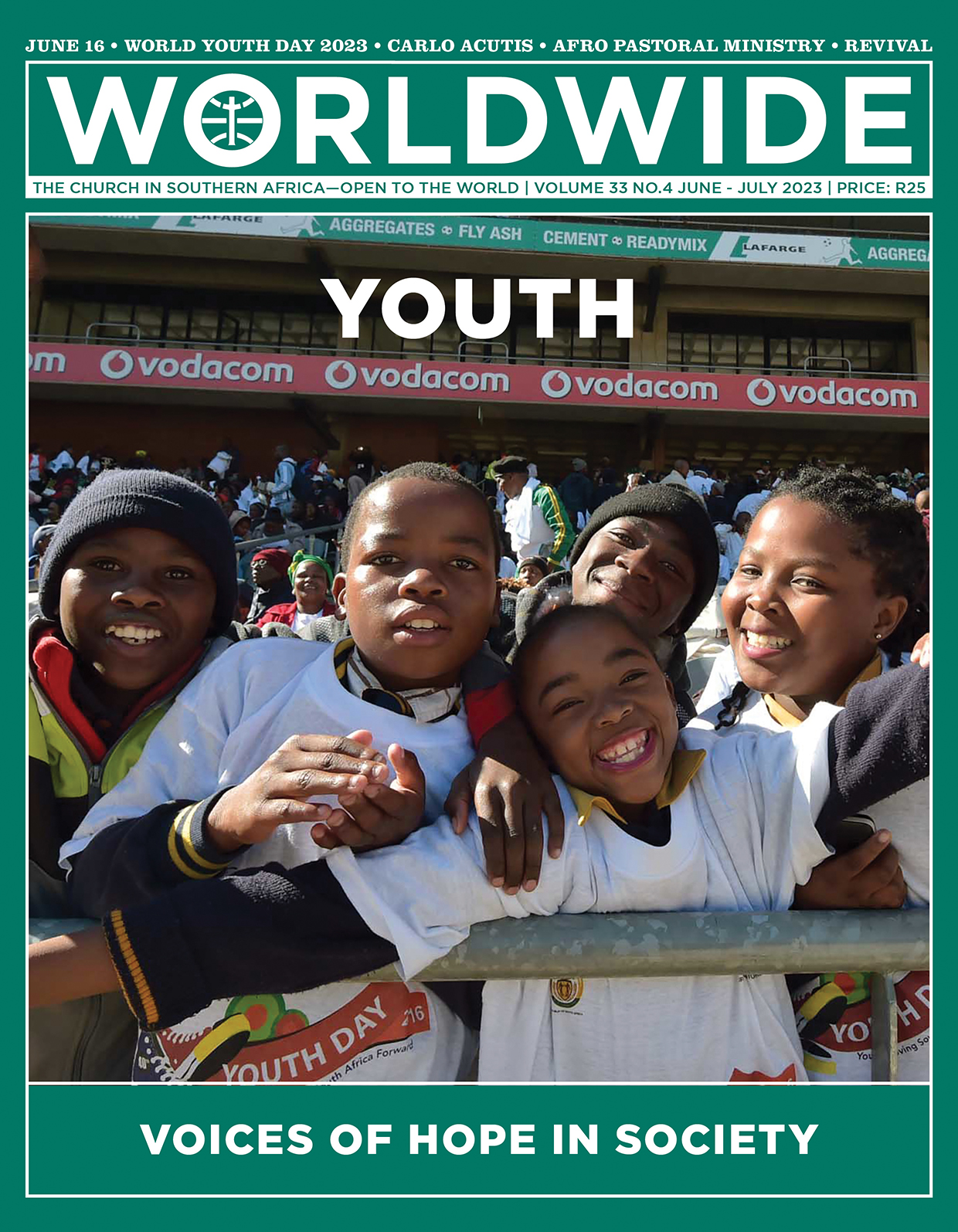

The front cover image shows youngsters commemorating Youth Day at Orlando Stadium in Soweto, the same location where an uprising against the use of Afrikaans as a vehicular language of education took place in 1976.

Some might see June 16 only as a public holiday, nevertheless, gratitude goes to those who strived on behalf of the youth for an inclusive and better education. Many youths today still face great challenges and need strong support in order to receive an integral formation which prepares them for a bright future.

FRONTIERS • AFRO YOUTH PASTORAL MINISTRY

A LIBERATION JOURNEY

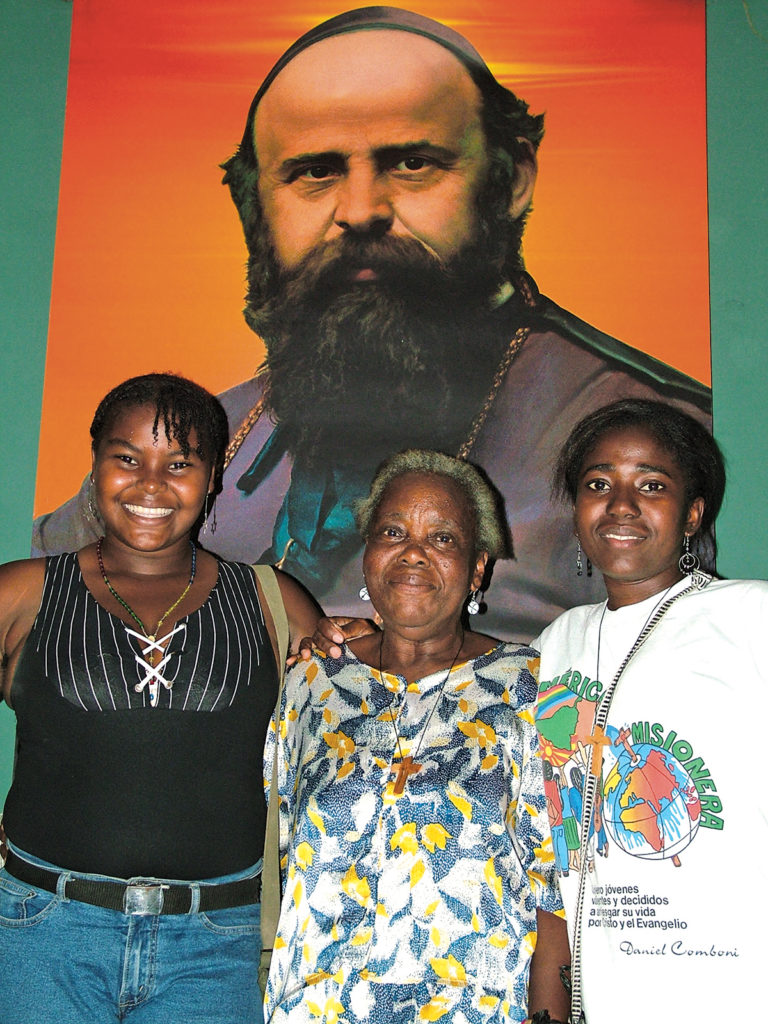

Mexican Comboni Brother Joel Cruz shares his experience of pastoral accompaniment of the Afro-Ecuadorian (Afro) people, particularly the youth, as they journey towards their integral liberation and the recovery of their identity

BY BRO. JOEL CRUZ MCCJ | GUAYAQUIL, ECUADOR

WHEN I arrived as a missionary in Guayaquil, Ecuador, in 1997, many young Afro were grouping together on street corners, in vacant lots or abandoned buildings in our area. They seemed to be aimless groups, without purpose or raison d’être (reason for being). They were seen as a social problem, like criminals, that instilled fear in those who passed by them. They were labelled as evildoers because of the colour of their skin. When they were seen together on public transport, in the streets, in parks or shopping malls, the police would immediately come to watch over them and people would move away from them.

The path of imitation

Society was unaware of the harm it was inflicting with those attitudes and the effect on these young people who, in various ways, felt that they were not considered human beings or equal to those who did not wear the colour of Africa on their skin. They suffered urban pressure to abandon their human, spiritual and cultural roots and to root themselves in a history, religiosity, spirituality and culture which was not their own. This feeling of being foreigners, even though they were Ecuadorians, forced them to follow the path of imitation to be accepted as ‘normal’ citizens and to have access to the opportunities of citizens who were not of African descent.

Imitation is the way of not being oneself, but being the ‘other’, whether freely or obligatorily. This reality of the youth made me think of a pastoral approach which could add support to being oneself, to authenticity, in the originality planned by God Himself. The Afro Youth Pastoral Ministry was then born.

The key that opened the door to the process of liberation of the young Afro was street conversations, where they gathered

Its starting point was the realization of not being oneself, just as the slaves in Egypt (book of Exodus) were deemed to be not people, not human, not worthy, not citizens, but what the emperor and the imperial society dictated for them. The key that opened the door to the process of liberation of the young Afro was street conversations, where they gathered. Starting from the book of Exodus, I began to insert the history of their ancestors, testimonies whose lights and shadows led to their present situation.

History as Gospel

The young Afro-Ecuadorians I met did not want to look at themselves because they were told, and learned by experience in society and the Church, that being black was not good, but a personal and social problem, which did not give one the dignity which a non-black person had. They were convinced that everything which portrayed African roots had to be abandoned; they despised themselves, as is reflected in this phrase: ‘I’m bad, you’re good. I want to be the ‘other’, to look like those who are more valued in the Church and in society’.

As missionaries, we believe that the Word of God has the power to transform a tragic story into a sacred one before which ‘one must take off one’s shoes’, like Moses, so as not to trample on it and damage it. God was there, is there and will continue to be there, walking in that history which is not ours. Our mission is to help the Afro-descendants to dust off their tragedy so that they can see the Gospel and become aware of their divine originality and of that first dignity which comes from the very being of God. This is a long process because it is difficult to expel the demons (evil counsellors) which sowed negative convictions in them.

Minds chained to lies

It is not true that an Afro-descendant does not have the same human dignity as those who do not have African roots. This is a religious, social, cultural, and spiritual lie but the historical and socio-cultural demons with which they lived convinced them that this was true. History convinced them that their roots were entrenched by the slavery of their ancestors and that, therefore, they had the last place in society and in the Church. That is why their minds were chained to ‘I can’t, I don’t know, I don’t have and I am not taken into account’.

This mental chain was imposed on the experience of the slaves who had no power, who were denied knowledge, who could not own anything, not even their own body, let alone have a say in their decisions, even about their own life. Dependence became the face of their existence.

I began to understand my role as a missionary among them, following the pattern of Moses: to leave the fortresses of the empire and the Pharaonic religion, to convince the ‘slaves’ that their condition is neither worthy nor pleasing to God, to teach them to dream of a different reality (Promised Land), to encourage them to set out on the road following a new horizon: more dignified, fraternal, just, more human and more divine.

Feeling sent

The time I spent walking with the Afro-Ecuadorians made me understand that their pastoral journey does not end when they recover their dignity and have better opportunities in the Church and in society. The final aim is to make them feel sent to share their being, their spirit and their experience of God, namely, to be missionaries in a world marked by negativity, discrimination, exclusion and diminished dignity. Someone who experiences all this, personally and collectively, and reads this experience, seeking the Gospel in it (the Good News), is better equipped to accompany those who are religiously and socio-culturally marginalized. The process that we call the Afro-Biblical Way aims to rebuild their image and likeness of God, the one that history, theology, philosophy, sociology and pastoral care itself have destroyed in different ways and for different reasons. It is a road that must be travelled from their history, not ours.

The road travelled with the Afro in Ecuador taught me that evangelising means helping people to turn their gaze to their history, a pilgrimage in time and space, in flesh and spirit, with many why’s, what for’s and how’s that the evangeliser must capitalise on to make the Afro-descendants understand that their skin is not a colour, but a history full of lights and shadows, and that in the end, it is the Gospel that God has for them.

This evangelical approach to their history caused pain, anger and rage, opening historical, socio-cultural and religious wounds which had not yet been healed, but a missionary has to help them to see the light that shines in the midst of the shadows of society, of the Church, of their reality and that this history—seen as a tragedy—should be seen and lived as Gospel (Good News).

I witnessed how they rediscovered their history, took up their palenques, their social, religious and political runaways, began to pick up the clothes of slavery of their ancestors and understand their deep mechanisms of resistance. The spirit of fortitude of their ancestors was lifted and they put it back on, but now with dignity to make their existence and their being visible; what was a source of shame and inferiority, became strength, richness and greatness for a new identity in society, in the Church, dressed with pride and freedom.

Understanding that God is also black

It took me 13 years of journeying with the Afro-Ecuadorians to help them approach their history and experience from the perspective of the Gospel. I witnessed how they discovered and accepted that God was not only close but that He became flesh in them and they were able to say that God is also black. That is how they understood that to be of African descent is to be a human being as worthy as God, and that is why negative complexes had no reason to exist.

Evangelisation among the Afro-Ecuadorian is not complete if we remain only in their experience of slavery as roots and origin. Their roots go beyond the memory of their flesh and spirit which speak of a hidden, unconscious, rejected, unknown source, of a theological, human, spiritual place, a place which does not always want to be reached: Africa; a place—socially shown—as being of human, spiritual, economic and cultural destitution, often rejected, denied and hidden. This is very painful and, even if one knows the Gospel and finds God in one’s history marked by slavery, if one does not rediscover and reconcile oneself with Africa, liberation will never be possible.

A journey of return

This anthropological, social, religious, spiritual and cultural journey to the place where their ethical-mythical core is found, continues moving and governing them when they make drums, marimbas, maracas or when they listen to their sounds, and their body speaks to the society and the Church in a different spirit. This journey has to be done because otherwise, they will not encounter the face of God revealed to the Afro people. This treasure, which the world has the right to know and to be enriched by, will remain buried in the complexes which shackle the Afro. This journey makes possible to understand the mystery of the incarnation of God, who became a human being in black flesh, who thinks, feels, acts and looks at the human being and the world as black. This is the highest point of the evangelisation of the Afro and, therefore, of their pastoral care.

Their skin is not a colour, but a history full of lights and shadows, and that in the end, it is the Gospel that God has for them

Certainly, this journey of return to Africa is not made to remain there, but to return enriched, more ‘black’, more strengthened, more original, more unique and only in this way will they truly be a richness for society and the Church. Otherwise, they will be lost in anonymity, in social and ecclesial invisibility.

Helping to put on African clothes

When the Afro abandons the dress of a slave, which he presented as his own, and begins to put on African attires, the evangeliser can say that everything is accomplished, because the rest belongs to the Afro. It is up to them to insert themselves as human beings—with riches that come from afar which this society and this Church need, in order to grow in spirit and truth. When one reaches this point, there are no more reasons for demands, one doesn’t want to be more than that human being that God has created in diversity; not someone else, but the black man that God made with His hands. Universal fraternity becomes the visible face of those who share what is their own with other fellow human beings who are different from them.

Dressing in African clothes is not something superficial or folkloric, but theological and spiritual, which becomes the motor of a new existence and co-existence. Diversity becomes richness and not a threat or competition. The Our Father is prayed in fraternal co-existence with those who are different, sharing differences.

The Afro Youth Pastoral Ministry entails accompanying human beings whose ancestors were uprooted from Africa and arrived with only their body and their memory. From that memory and corporeality, the missionary assists them in re-awakening, far from Africa, the human being that God formed with His hands—taken African soil and infusing His Spirit in it so as to become incarnate.

The Afro are not African, but they are also children of Africa. They must accept, recognise, digest, drink from that hidden well, far from the life of the Church, almost in hiding, because perhaps the Church has not always been able to see that in that flesh and in that spirit, the mystery of the incarnation was also realised. The Afro pastoral accompaniment must cultivate and safeguard this work of God in order to offer it to the world.