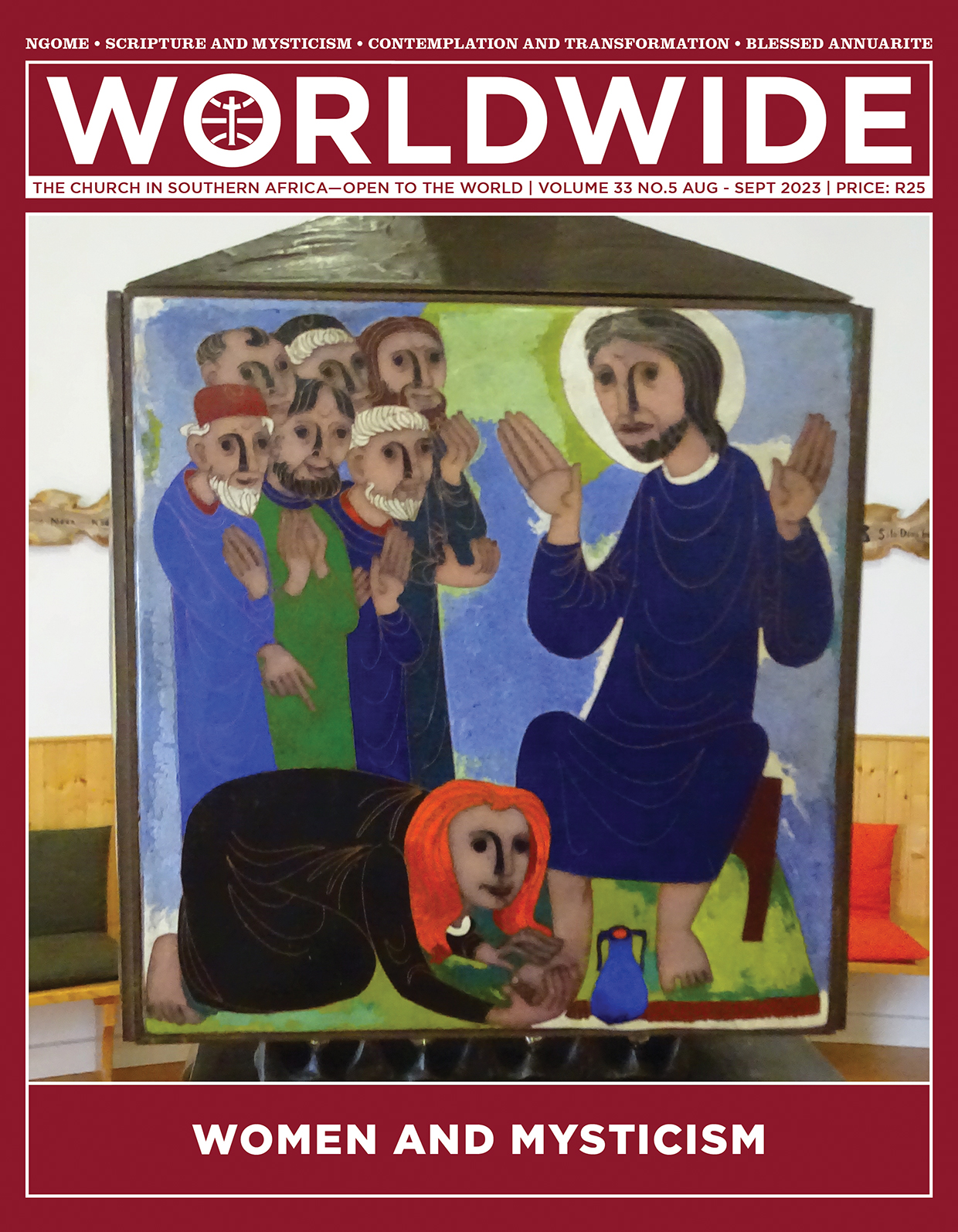

WOMEN AND MYSTICISM

Mary anoints Jesus’ feet at Bethany (John 12:1–8). The scene is part of a series which represents passages of women with a prominent role in the Scripture. The decorations are placed around the sides of the Tabernacle in the Chapel of Meditation at the University of Mystics in Avila, Spain.

Mary listens to and manifests her love for Jesus. Contemplation becomes the mesh in which her Spirit-led actions find their meaning and support.

SPECIAL REPORT • THEORY OF ATTACHMENT

Mystical experience: “being with” the other

We are relational by nature. Relationships are part of our DNA and an essential constituent of any human being. We could even say that before being “rational”, or developing our reasoning capacity, a bond must have been formed. We are born to enter into relationships, being that a necessary condition for our brain to mature and for our own survival

BY MARIA NOEL FIRPO | psychologist, Segovia, Spain

THE THEORY of attachment (Bowlby 1969), illuminates our “being in relationship”, understanding human development as a relational process. Attachment, which has nothing to do with being “attached” to something or someone in a negative way, is “any behaviour by which an individual maintains or seeks proximity to another person, considered stronger and more capable. It is also characterised by the tendency to use the primary caregiver as a secure base from which to explore unfamiliar environments and to return to as a refuge in times of alarm” (Bowlby, 1980).

Bond of security

That primary caregiver, at best our mother or father, is the one who takes us out of our stressful moments—hungry, sleepy, cold, etc.—when we are babies. The experience we have when we feel bad, and someone responds to our call, gives us a feeling of protection from the world around us. It regulates us emotionally, generating basic confidence that our discomfort will be calmed, that it will not last long and that with someone we will feel better. The opposite can be devastating. This primary bond is necessary for human survival, as social beings, sensitive, connected and capable of relating to others.

These mutual exchanges that take place between caregiver and baby, after a while become internalised, achieving what is called an “internal operating model” (Bowlby, 1969), which will become a way of being in relationship, of “being with the other”. The attachment experience does not remain only as a memory but continues to be present, transferring to other relationships. Such internal operating models organise the subjective experience, and lead us to ask ourselves: am I worthy of being loved, will the other person listen to me, will he/she accept me, will he/she be interested in what I say, will he/she come to my aid if I need him/her, and so on.

The answers to these questions will be based on the experiences we have had. Therefore, our identity, besides being intrapsychic, is intersubjective.

We have the potential to transcend the limits of our own history, breaking the chains that transmit insecurity, mistrust, fear, etc

It is expected that the baby has a “safe base” to turn to, knowing that the adult will quickly respond, be good enough, provides support, regulates the moments of alarm and together with him the longed-for calmness returns. We need this in different ways throughout our lives. We are always fragile and in need of others. If we have been moderately satisfied, with the presence of an optimal, sensitive and contingent primary caregiver, we can feel safe with others, be ourselves and be confident. Otherwise, if the person has not been sensitively cared for, or if he does not have the certainty of having been loved, he will establish relationships with the illusion of obtaining love, consideration and attention. He will live with this thirst and we can see the consequences. He/she will be waiting for the attachment figure not to abandon him/her, using any kind of strategy to achieve this or otherwise, “disconnect” so as not to resort to it. All this is very complex and exceeds the scope of this article, but it is part of the needs, desires, anxieties and interpersonal dynamics, which will accompany us in our relationships with others.

Not determined

Although attachment occurs throughout our lives, the person with whom we have this relationship varies. At the beginning it is the parents, as we grow up it can be a teacher, a friend or a partner; we ourselves may be attachment figures for others, but the function that is fulfilled is always the same: to provide support, to calm and to regulate emotionally. The most encouraging thing about all this is that if the experiences have not been positive, those patterns can be modified in the light of new bonds. We are not determined.

To argue this, we rely on neuroscience, specifically “neural plasticity” (Ansermet, F, and Magistretti 2006), as the brain’s ability to be modified by experience. With a new experience of a deep bond, the traces of a previous one can be transformed. Where there is an authentic person-to-person connection, each time more special, deeper and unique, that relationship is transformative as new ways of “being with” the other emerge. This invites us to believe that we have the potential to transcend the limits of our own history, breaking the chains that transmit insecurity, mistrust, fear, etc.

This applies to us, but we also have the possibility of helping to change dysfunctional patterns in the people we relate to. In this way, the attachment theory helps us to understand how our bonds make us who we are and how we put ourselves into play in our relationships with others. St John of the Cross says: “Alas, who can heal me” (C6). It is not a therapy, nor a medicine, it is a relationship with someone, who always repairs and heals.

Teresa of Jesus, master of interpersonal relationships

Relationality, moreover, is the central characteristic of the God of Christians. Created in the “image and likeness” of a loving God, of a Trinitarian God—three persons in relationship— we could say that “we are relationship”. This is expressed to us by the mystics, people who know the mystery of divine communication to the point of living an intimate and close relationship with Him. They feel fully loved by God, accepted and welcomed by this community of divine persons. They experience that God has the face of one who only knows how to love. Mysticism is the science of love.

Teresa of Jesus, a nun, woman and mystic of the sixteenth century, knew how to go beyond the walls of the cloister with her foundations, her writings, and with her extraordinary ability for relationships. This also helped her in her relationship with God. She tells us that she was a favourite daughter, that the sisters valued her for her sympathy and her joy in service, that she had grace in her conversation, and that this made her feel loved, “I used to be a friend of those who loved me well” (CC3,2). In her letters, we see that she was as much at ease with merchants as with the King. She lays bare her soul shamelessly before her readers, her sisters, confessors and inquisitors. Knowing that she is loved by others and by God generates in her a basic confidence that overflows her. The human being learns to love by first being loved by those main caregivers we have seen. In the spiritual life, it is also like this: we become aware of the previous loving attention of God, and after that comes the human response to the divine initiative. This is God’s style: He loves us by making us capable of loving.

God: Secure attachment figure

Teresa only wants to tell of the wonders that God has done for her. She invites us all to experience this transformative relationship, knowing that if we are truly committed, we will not be disappointed. She brings us closer to a God who is permanently desiring to relate to us: “Never, daughters, does your Bridegroom take His eyes off you…He is not waiting for anything else but for us to look at Him, and He is so pleased when we look at Him again, that His willingness for it is never short “ (C26:3). If we connect it with what we have discussed about the attachment theory, God would be a secure attachment figure, with whom we could experience a relationship in which there is someone capable of loving us unconditionally as we need it. Approaching Him and relating to Him, transforms us. A religion based on a set of pious practices does not make us better people, but what transforms us is the intimate encounter with God. In the mystical life, He is always the protagonist, the One who goes ahead. If our relationship with God does not result in a renewed self, a recreated being, all our actions are worthless. It is the being that must be recreated, from egocentric to other-centric. And we cannot achieve this alone but in relationship.

Prayer as friendship

As a teacher of spirituality, St Teresa speaks of prayer—attached behaviour—as “trying to be friend, often in solitude, with the One we know He loves us” (V8,5). Friendship is the term with which she defines her relationship with God. She relates her experience telling us that as a consequence of it, her life was “much improved and stronger” (V28,18), “…I saw myself as different in everything” (V27,1).

A relationship of acceptance and self-giving. Recollection shapes our personality. Teresa of Jesus teaches us to become aware of a Presence: Someone who is with us, but who surpasses us, and who, at the same time, leads us to our authentic true human being and to our neighbour.

The beginning of mysticism is the beginning of that “other life, a communion of longings and labours with Jesus. Teresa never loses sight of the fact that the glory of God is the salvation of the person, understood as the assumption of the communion of the Trinitarian life, to participate in that relationship. She clarifies that the mystical path does not consist in building “towers without foundation”, but to grow in love. “It is not a matter of thinking much, but of loving much” (4M1,7). Her style is always very plain, direct and without affectation, even when she speaks of spiritual themes. The essence of her mysticism can be summed up in “no, sisters, no; works, the Lord wants, and if you see a sick person to whom you can give some relief, do not give yourself to anything and lose that devotion…” (6M 3:11). The Thou of God will always refer us to our neighbour, to our brother and sister. The mystical life does not exclude anything that integrates human life.

If our relationship with God does not result in a renewed self, all our actions are worthless

Friendship does not have a totalitarian term, it is always on the way, so this process never ends in this life, we will always be committed to more. In this way, relationships grow in interiority, they are healed and we live more fully in our constitutive relationship with God. That God who is never exhausted, who is always a Mystery.