JOURNEYS OF LIFE

The painting on the front cover entitled “The disciples of Emmaus” reflects our journey of hope. Jesus not only walks with us, but gives us the wisdom to perform our ministries and opens our eyes to see Him in the people that we are serving.

PROFILE • ST AUGUSTINE OF HIPPO

A JOURNEY TO THE INNER SELF

St Augustine, one of the greatest figures of Christianity, journeyed a tortuous path until finding his True Self. Through the road less travelled he reached a destination of a fulfilled life and left an inestimable legacy for the world.

BY Marian Pallister | Chair of Pax Christi Scotland

IN OUR naivety, we cling to that childish belief that all saints arrive on this earth pure and holy and grow in that unblemished state to carry out the work that leads to their canonisation. Even when we learn of their backstories (St Peter made some serious errors even while he was so close to Our Lord, and St Francis of Assisi led his family a merry dance and seems to have been the archetypal rebellious, pleasure-seeking youth until the Holy Spirit reached out to him), we perhaps don’t fully understand their journeys to an inner self that becomes the bedrock of a life worthy of sainthood.

The road Augustine was on in his early life was clearly one that gave him much pleasure.

Let’s consider, then, the life of St Augustine of Hippo—a saint considered appropriate to be the patron saint of brewers because of the wild life he indulged in before his conversion led him on a different path.

The poem The Road Not Taken by Robert Frost springs to mind when considering the life of Augustine. The poem’s narrator says he is sorry he could not travel both roads when he came to a junction in the path through the woods. The road Augustine was on in his early life was clearly one that gave him much pleasure. He is, of course, famously quoted as saying: “Grant me chastity and continence, but not yet.” It’s a line that brings us a wry smile, but then we have to consider the immense body of St Augustine’s work that has influenced Christianity for two millennia and reflect that once the journey takes a right turn, there is no limit to the positive experiences to be encountered or the splendour of the prize at the journey’s end.

Family origins in present time Algeria

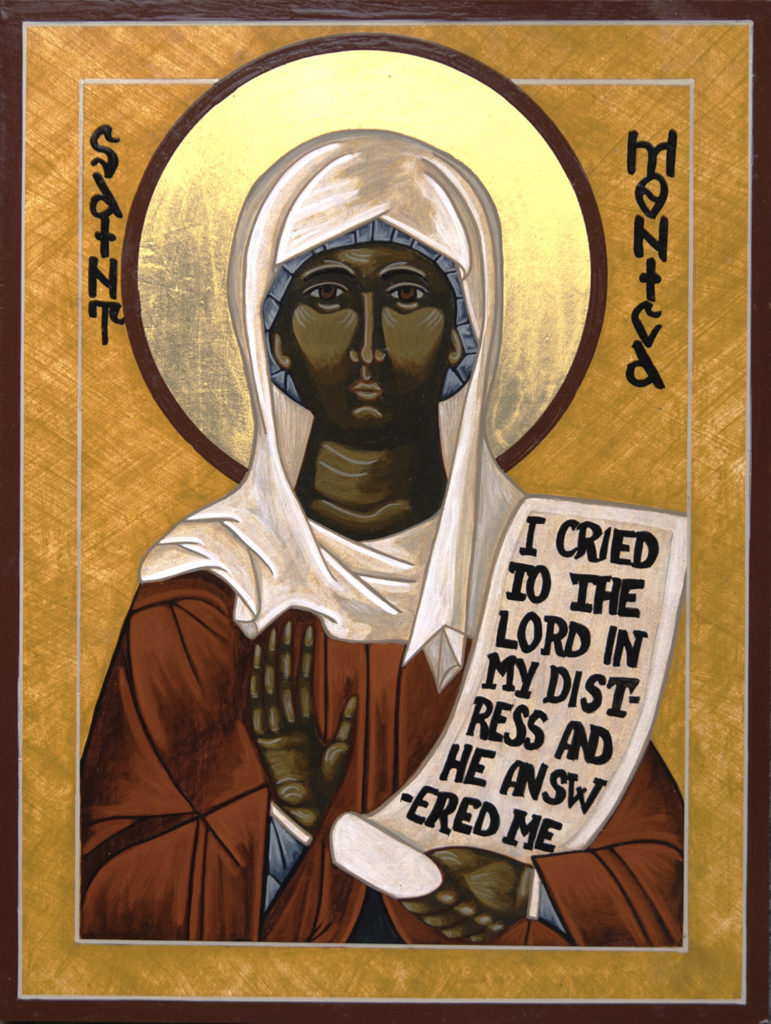

Where did the journey begin for Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis, to give him his Latin title? He was born on 13 November 354 in Thagaste in the Roman province of Numidia. Today, that is known as Souk Ahras in Algeria. His mother, Monnica (known to us as St Monica) was a devout Christian and his father, Patricius, was a pagan who did not convert to Christianity until he was on his deathbed. Augustine was one of three siblings, all of whom spoke only Latin, although Monnica was of Berber descent. The family name meant that Patricius was descended from freedmen of the Aurelia people who were given Roman citizenship under the Edict of Caracalla in 212.

Augustine went to school in what is known today as M’Daourouch, some 20 miles from home. He was taught Latin literature and a range of religions. Even as an eleven-year-old, he discovered the thrill of committing a crime, recording in his autobiographical Confessions that he stole fruit because “it was not permitted”, rather than out of hunger, admitting that he loved the excitement of that stealing spree.

Self-indulgent life in Carthage

By the time he was in his late teens and studying rhetoric in Carthage, he was enjoying a decadent lifestyle that included sex, alcohol, and whatever was the 370s’ equivalent of rock’n’roll. It wasn’t only his behaviour that upset his mother, who had raised him as a Christian. Joining the Manichaean religion that originated in Persia and was prevalent at the time across the then known world, was clearly a great disappointment to Monnica. He also caused her anxiety by having a relationship with a young Carthaginian woman—they were a couple for 15 years and had a child together. A second similar relationship ended when marriage to a wealthy young woman was planned for him. The wedding did not take place, however, because Augustine’s journey was now taking him in a very different direction—to become a Christian.

How did he reach that junction?

Despite his wild oat sowing, the student Augustine was intellectually bright and he went on to become a teacher, first in Thagaste and then in Carthage. Ironically, it was the unruliness of the students in his school of ethics that made him move to Rome. Even there, uncooperative students made life bleak. Networking, however, led him to one of the top positions in the Roman world. His Manichaean contacts introduced him to movers and shakers who knew of a vacancy for a rhetoric professor in the imperial court in Milan, and in 384 he got the job.

Conversion to Christianity

Despite the help of his religious friends, Augustine now had doubts about Manichaean theology and drifted through various religious schools of thoughts before meeting with Ambrose of Milan, the theologian and statesman who was Bishop of Milan from 374 to 397 and of course, in time became a saint himself.

Ambrose steered Augustine on his journey towards Christianity, and probably was most influential (along with his mother Monnica, who had followed him to Milan) in guiding him on the journey to discover his true inner self.

First came friendship between these two masters of rhetoric. Augustine didn’t expect to find answers in any religion at that stage of his life. And indeed, it was now, as he wrestled with his relationship problems, that he made that famous comment about being good but not yet.

His meanderings through loose living were cut short in 386 and the journey took a sharp turn towards Christianity.

The “yet” perhaps came quicker than he expected. His meanderings through loose living were cut short in 386 and the journey took a sharp turn towards Christianity. He recorded that he heard a child’s voice telling him to read, and randomly opening St Paul’s letter to the Romans he found in Chapter 13, verses 13-14: “Not in rioting and drunkenness, not in chambering and wantonness, not in strife and envying, but put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh to fulfil the lusts thereof.”

Now that was a signpost hard for a man like Augustine to ignore. He followed the arrow and during the Easter Vigil of 387, Ambrose baptised him and his son Adeodatus. Following the route initiated by St Paul, Augustine developed his Apology—his personal defence of Christianity—over the next year, calling it On the Holiness of the Catholic Church. He no longer wished to teach rhetoric but to live a life of prayer.

Monastic founder and elected Bishop

On his return to North Africa, Augustine, Adeodatus, and several companions lived that life, sharing their insights about Scripture and the Christian vocation. Three years later, however, he travelled the 50 miles to Hippo, and there was called to be a priest. This wasn’t what he expected—this was surely a wrong turn? But he accepted what he believed was God’s will for him as the journey to his inner self took yet another turn.

He founded a monastic community in Hippo, which he directed while assisting the bishop, Valerius. He then succeeded Valerius in the mid-390s, writing his Rule for the monastic order so that the brothers could continue their lives when he moved into the Bishop’s house. He established a third community for clerics in his new home.

This was “yet”. Augustine was now happy to leave his former life behind and follow a monastic style of life in community, giving away all his possessions. He did, however, continue to use his rhetorical skills, becoming a renowned preacher of homilies which (perhaps unusually for the day) were recorded. There are still some 500 available to us today.

Great Communicator of Theological and Social issues

In our most modern methods of communication, we follow Augustine’s example, using metaphors and similes, analogies and repetition. What politician has not stressed her or his point by repeating a well-turned phrase? Nelson Mandela’s “Let there be justice for all…Let there be peace for all” could be straight out of Augustine’s playbook. His stagecraft also helped him achieve what he believed to be most important for any preacher: to ensure the salvation of his or her audience. Life for Augustine was no longer about himself, but about those he set out to save.

Some of his ideas are incredibly modern. For example, Augustine believed that the book of Genesis was simply a device to help us understand the idea of creation, which to his thinking would be incomprehensible to humans. His concept that Christ rules the earth spiritually (rather than returning to earth to establish an actual 1000-year reign, as was a belief during his time) was adopted by the Catholic Church in the Middle Ages.

It was his understanding that—during Consecration—the bread and wine do indeed become the body and blood of Christ, referring in his On Christian Doctrine to the Eucharist as a “figure” and a “sign”.

Some of his thoughts were, of course, purely of his time, but held sway down the centuries. His (revised!) notions on chastity and sexuality shaped Church doctrine. His teaching that virgins raped at the Sack of Rome were innocent because they did not intend to sin and did not enjoy the act is a concept that some courts of law in 2023 should consider.

His meanderings through loose living were cut short in 386 and the journey took a sharp turn towards Christianity.

Augustine believed that Christians should be pacifists, but made an argument for a “just war” which only in the 21st century is being contradicted in favour of nonviolence and dialogue. Augustine’s time was, of course, very violent. The German tribe known as the Vandals invaded Roman Africa and in 430, they attacked Hippo. Augustine was ill, but it was now that one of the miracles that led to his sainthood was performed, when he healed a sick man.

A legacy which made all the difference

They say that, knowing that death was approaching, he excommunicated himself in an act of penance and solidarity with sinners. Be that as it may, he is recorded as spending his last days in prayer and repentance, weeping as he read the penitential psalms of David.

Before Augustine died on 28 August 430, he had asked that the library of the church in Hippo and all his works and those of others be preserved. Surely it was another miracle that the Vandals, having retreated, then returned to Hippo and burned the city. Everything went up in flames except Augustine’s cathedral and library. It is fitting that as well as being the patron saint of brewers, he looks after printers and theologians.

The final stanza of the Robert Frost poem is:

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less travelled by,

And that has made all the difference.

Augustine’s decision in choosing the road less travelled certainly “made all the difference”, clearly enabling him to find the inner self that led to sainthood.